TechBio

TechBio: The Role of AI in Drug Discovery

Exploring how TechBio and AI are redefining research, development, and innovation in healthcare.

Table of contents

The role of AI in drug discovery

What are the pain points in drug development today?

What can AI optimise, and where are companies focusing?

What are potential pitfalls of using AI for drug design?

How should we view the current field?

What a Great “TechBio” Company Looks Like

What makes “good data” for AI/ML?

What business model to use?

Therapeutic considerations

Key takeaways

Authors in the Team: Maya Misra + Elia Stupka

In 2020, there was a surge of interest in biotech investing due to Covid, and this coincided with the rise of functional AI tools. TechBio emerged as a field with the goal to use AI to improve drug development time, cost, and approval rates.

After significant investment in 2020-2021, the momentum has appeared to slow as companies struggle to demonstrate the results of their investments. The biological value of AI can feel opaque, and valuation expectations can be disjointed between the tech and bio sides of the field.

At Angelini Ventures, we wanted to dive deeper into the market, understand the real purpose of AI in drug development, and create a framework of success for TechBio companies.

What are the pain points in drug development today?

How can AI address them?

Researchers developing drugs must navigate the vast complexity of human biology - predicting how a small molecule will behave among thousands of proteins, metabolic pathways, and cellular interactions. Expert academic understanding can provide the idea for a drug, and skilled translational scientists bring it through development, but still it there are multiple pain points.

We envision AI as assisting with the following pain points:

Drug development takes time

and is costly

10+ years to marketIt takes around 10 years to validate a target and develop a lead, and additionally 5-8 years more to bring a drug through the clinic. This costs a biotech on average $25-40m for the preclinical stages, and upwards of $100m to run trials.

In-silico AI approaches coupled with high-throughput wet lab techniques have the potential to optimize efficiency

However, developing an AI tool takes upfront time and cost which must be considered

Success rates are low

even for promising candidates

<15% average success rateThere is an average 15% success rate from IND submission through approval. With limited ability to predict drug interactions in complex systems, translatability suffers

Machine learning can use data to better predict outcomes and prioritise drug candidates

Innovation requires novel solutions

AI enables exploration beyond conventional scientific approaches

We trend toward the same targets and same modalities, but that’s not how blockbuster drugs are made

AI can offer ‘un-intuitive’ drug design exploring new chemical spaces and modalities

We have too much data

to handle

AI can uncover insights hidden in complex,

unstructured biomedical data.

Advances in genomics, proteomics, and other fields has generated a wealth of data, but it’s poorly harmonized and difficult for a human or simple algorithm to parse

AI could search for patterns across multiple data types and synthesize novel findings that inform molecular targets, patient populations, or unique biomarkers

Any AI tool will need to show a meaningful improvement along these metrics, particularly success rate, time, and cost.

When we look at what current AI-driven biotechs are focusing on, they are largely geared towards optimising in-vitro preclinical work to create better candidates, including finding better targets or enabling novel modalities.

There are fewer companies working directly on in-vivo work or clinical trial optimisation, even though these are areas with the highest failure rates and lack of understanding. However, increased complexity and poorer data quality and quantity inhibit the development of AI tools for these stages of development.

| Stage | AI Solutions | Limitations | % of companies |

|

Target identification |

- Literature data mining - Integration and analysis of –omics datasets - Disease modelling, ‘virtual organs’ |

- Quality and quantity of dataset contributing to understanding of disease can vary

|

15% |

|

Target validation |

- Dynamic modelling of binding pockets, pathway interactions - Identification of biomarkers

|

- Must be validated by wet lab results

|

|

|

Lead discovery |

- Rapidly screen wide chemical space - Dynamic modelling of interactions, kinetics, etc - Generation of un-intuitive options

|

- Best supported by high-throughput screening - Non-static molecular dynamics remains difficult for AI to model, but is crucial to understanding drug binding

|

80% |

|

Lead optimisation |

- Optimise within parameters of toxicity, selectivity, bioavailability, etc

|

- Best supported by high-throughput screening

|

|

|

Preclinical testing |

- Virtual animal models

|

- In silico translatability to animal models is unproven - In vivo timescales limit quantity of data that can be acquired to train ML

|

3% |

|

Clinical trial twins |

- Integrate and analyse more patient data; subpopulations - Digital twinning: control group is digital version of treated patient

|

- Long regulatory path to digital twins

|

2% |

For this and following data, we analysed 100+ AI drug development companies in Europe and the US, which were representative of the overall distribution of clinical stage and funding status. We excluded SaaS companies whose primary focus was to sell a drug discovery solution.

Data requirements

it may be difficult to acquire high quality data at a critical mass to train a model; data must be well-labelled be fit for purpose;

Bias

a dataset which is a poor reflection of reality leads to biased results, with ethical implications. Advances in precision medicine may only be ‘precise’ for a certain group;

Development cost

significant costs of recruiting talent and setting up compute and infrastructure, especially in an environment with heavy competition for tech talent. This may draw resources away from the development of drugs themselves;

Explainability tradeoff

growing demand for explainable models

for certain use cases (e.g., patient facing),

which may limit model capabilities.

The large players

Many of the largest AI players focus on broad foundational models and came to prominence during a time where interest in both AI and healthcare was high, and capital was readily available. Their key value offering is faster time to market and increased chance of approval. They aim to be the partner of choice for large pharma.

While some have had early “successes”, we do not view these as reflective of AI-driven companies. Some companies such as BioXCel have an approved drug but have in-licensed it rather than used their AI platform for development. There are a number of drugs now entering Phase 3 (Insilico, Nimbus, Compugen), and time will tell whether they are successful and, further, whether that success justifies the platform development costs.

We note there are some extremely early-stage initiatives with significant capital injection like Xaira and Isomorphic. They are immature but with significant talent and access to resources, and might be considered “too big to fail”.

The startup landscape

These companies are often preclinical/early clinical. Lacking the billion-dollar resources of the big players, massive foundational models are impractical. Instead, they must focus on a particular modality or target, and build a model particularly suited to the problem at hand, whether it is “explore chemical space of nanoparticle design” or “understand network effects of CNS drug”. Capital efficiency and not building a needlessly large model are key.

Startups can position themselves by having the relevant data to address their particular focus area, and by bringing together an expert team in both science and ML.

Considering the dual nature of good tech and good biology, we consider that “good” looks like the following:

Biotech

- Therapeutic area: Subject to same expectations as non-AI biotechs: disease of focus is relevant; market size established; target is validated; modality suited to disease, etc

- Application of ML: ML aims to solve a problem other tools cannot; whether a problem with drug development generally or challenges of a specific therapeutic area

Artificial Intelligence

- Compute: must secure appropriate processing power and critically evaluate how complex a model is required to be fit for purpose

- Data: ML algorithms are general and not protectable by IP. Good data is the rate-limiting factor and should be actively generated, acquired, and protected

- Explainability: the closer to a patient an application of AI is, the greater the desire that the model be explainable; less likely to be a problem in target ID or lead optimisation

Other

- Team: Talent in both biotech and ML; capable of simultaneously building tech infrastructure and asset pipeline. Best TechBios have a “hybrid” culture across both

- Data protection: AI faces regulatory pressure over source/protection of data; however life sciences field already well versed in data protection, so unlikely to be significant problem

On the flip side, what are some red flags to avoid?

Playing too safe: AI tweaks the edges of what we already know; these models offer minimal value if offering variations on known modalities or relatively well-understood diseases.

Silver bullet narrative: AI cannot solve everything, and the capabilities of an in-silico tool should not be overstated. Instead, the company must be able to succinctly describe the problem their AI platform solves for, and demonstrate validation in vitro/in vivo.

Bad data: use of static or externally acquired datasets; datasets that are disparately labelled; areas with sparse or poor-quality data, where assays or inputs do not meaningfully relate to the disease or drug design.

Bias: company uses samples from primarily Europeans, or particular cell lines or rodent strains, without accounting for specific characteristics of these models. The best ML is instead able to disentangle bias by accounting for these factors.

Ultimately, the requirements for a well-run therapeutics company apply to TechBio as well, and ML applications must be carefully designed to add value to therapeutic development. The strongest companies have truly proprietary ways of obtaining data and/or deriving insights from them.

An ML model is only as good as the data it’s trained on. It must be…

Fit for Purpose Inputs (imaging, biomarkers, etc.) must clearly correlate to disease in question. Areas with challenges in generating disease relevant data may prove harder, but also provide a stronger moat

Well-Labelled Data has both input (e.g. molecular features) and outputs (e.g. toxicity effect) to train ML, cleanly labelled

High Volume Advanced neural networks require large training datasets – Recursion dataset is >20 petabytes. However, there will be advances in AI to train on lower volumes of data.

Unbiased. Results are representative across cell types, tissues and organs, patient demographics/subpopulations

Updatable/Live Learning. The best ML models are able to update based on results fed back from wet lab experiments

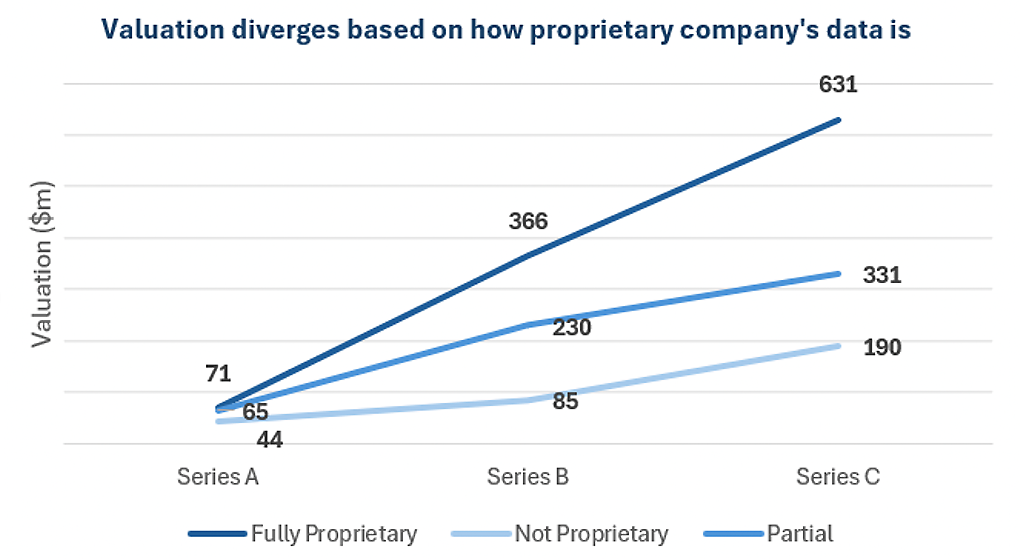

Proprietary data thus becomes a key value driver, and we see this reflected in the valuation a company receives.

Internal pipeline

Use AI to develop candidates, and take drug through development process themselves

Partnership model

Jointly conduct discovery and development with a large pharma, benefitting from milestone payments

SaaS-style

company offers a service to pharma to aid an aspect of drug development, with upfront fee and potentially milestone payments

Mixed model

Blend of own pipeline,

partnerships, and potentially

a service model

The internal pipeline model allows the company to capture full revenue potential. However, this requires all expertise to be in-house and has long timelines to revenues; in an environment that is increasingly skeptical and wants early proof-points from TechBios, this may present difficulties.

The partnership model addresses these concerns, as pharma can pay out milestones periodically, and also brings strong clinical expertise. However, there may be difficulties managing the additional team, and revenue potential is lower. Companies may also find themselves more at the whim of what pharma wants, and not be able to develop core capabilities. Nonetheless, partnerships bring additional value and contribute to exits.

A mix of partnerships and internal pipeline is advantageous as it balances control and revenue upside, brings in valuable expertise from established pharma, and faster validation and multiple shots on goal for the tech in the TechBio. Investors likewise value mixed models more than internal pipelines alone, especially as a company matures to the point it enters clinical trials—disclosed series C valuations for a mixed model have a median of $500m, while those with an internal pipeline at $340m.

In our review, we found the indications pursued by TechBios largely matched the general biotech landscape: areas like oncology and neurology are busy, with rare disease becoming attractive if a company has a particular solution.

For the purpose of training a model, busy areas like oncology have high data quality and quantity, well validated models of disease, and high pharma interest. On the other hand, areas like neurology are difficult to address but could benefit from targeted use of models with high rewards if successful. Where an indication is difficult, a differentiating factor for ML may be ability to generate unique insights from data.

it will take patient capital and committed investors

to mature the market;

while retaining control of their core assets.

Angelini Ventures

Angelini Ventures